Tim Hawkinson

Known primarily for his large-scale kinetic and sound-producing works, such as the monumental Überorgan, shown at the Getty in Los Angeles, Hawkinson has also created a bird skeleton from his own fingernail parings, a latex cast of his body inflated with air, and clocks fashioned from a Coke can, a manila envelope, and a toothpaste tube. His fantastical assemblages, which may include sculpture, painting, photography, drawing, or printmaking, suggest the profound strangeness of life, matter, and time. –Doug Harvey

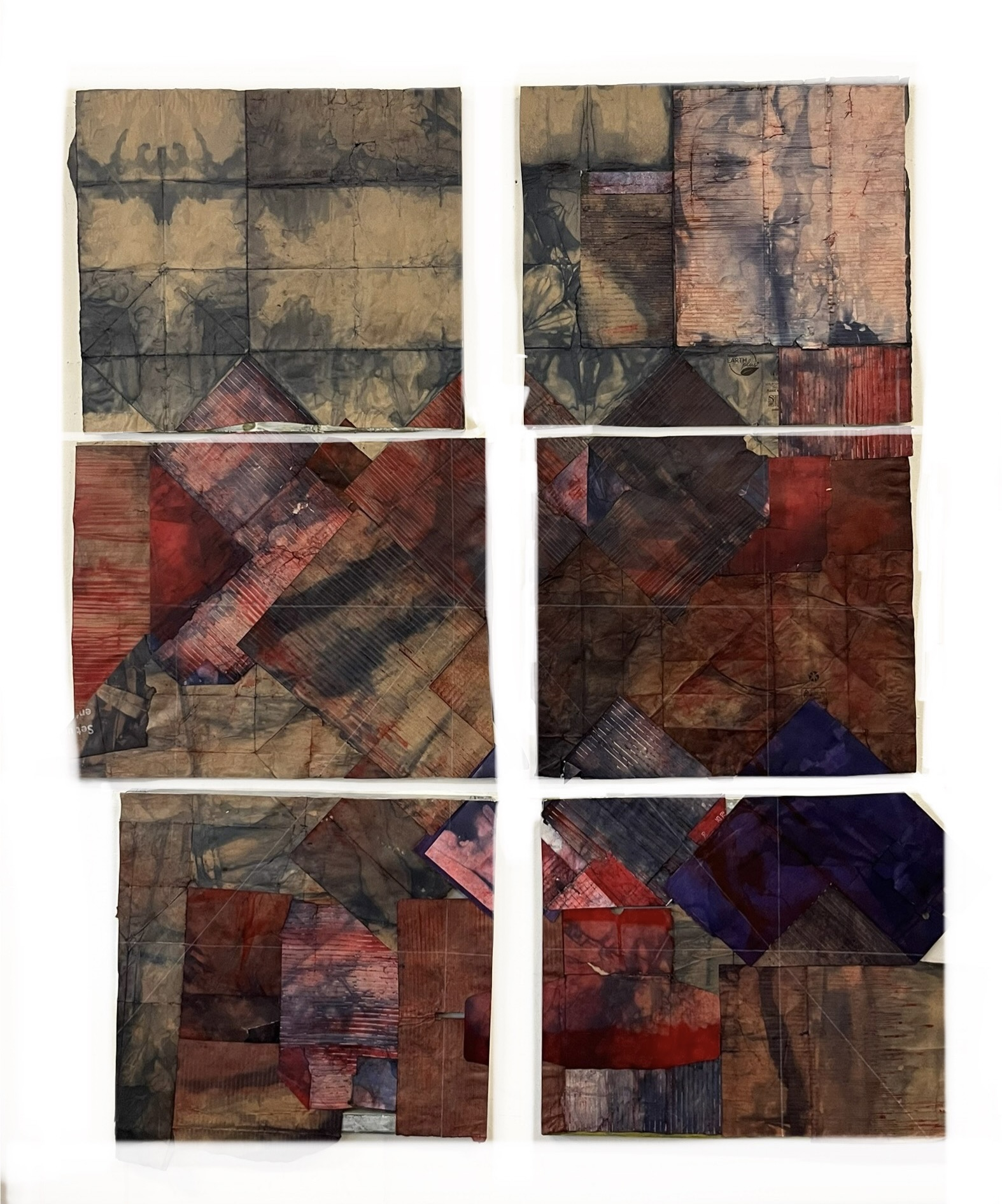

Jodi Hays

“I build collage surfaces from bleached and dyed cardboard. I sink recycled corrugated cardboard under a dye bath to reveal rivulets of color, making visible the box’s formal structure. My use of these materials accesses a relationship to resourceful labor which encompasses the rich visual vocabulary of sewing, piecing, and abstraction. While the work evokes weathered boards, humidity, beadboard, and found patterns in textiles, it also nods to Modernist making and the history of painting. I enjoy pairing art historical language with humble materials, the high with the low, bringing together contemporary and ancient notions of shelter, protection, and care.”-Jodi Hays

Frank Gehry

The Wiggle Side Chair is part of Frank Gehry’s 1972 furniture series ‘Easy Edges’, in which he succeeded in bringing a new aesthetic dimension to such an everyday material as cardboard. The sculptural chair is not only very comfortable, it is also strong and robust. It currently in production at Vitri in Basel Switzerland.

“I love working with materials directly. The cardboard furniture allowed that to happen. I could design a shape and build it in the same day. Test it. Refine it. And the next day build another one.” -Frank O. Gehry

“Cardboard furniture. What an albatross. Boy did I get myself in trouble with this one! It grew out of the need to find something cheap and disposable for fixtures. I started experimenting with cardboard in all the ways one would think of it in terms of efficiency; folded sheets make a structure very economically. Somehow, when you made something, it wasn’t very nice. It was folded cardboard. Then one day I was looking at architectural contour models, which were layers of cardboard. I was looking at the end elevation with its combed look, and I got excited about it. I started to see it as an aesthetic opportunity, and I made the desk I still use.” -Frank O.Gehry

Hector Dionicio Mendoza

Hector Dionicio Mendoza grew up with an appreciation for faith, ritual, and the environment. The artist’s multimedia artworks blend ideals of geography, memory, and labor. His use of cardboard boxes, cinder blocks, and other recycled materials, along with plants and natural imagery draws out these associations. Mendoza’s grandfather, a fifth-generation curandero (shaman) of Afro-Caribeño lineage, who practiced alternative healing traditions, was a pivotal influence on his artistic concepts, materials, and imagery. The foundation of his artistic practice is rooted in the Indigenous Purépecha people’s reverence of ancestors and spirits in nature as well as the religious and spiritual concepts of Catholicism, shamanism, and ethnobotany.

He is represented by Luis de Jesus Gallery in Los Angeles.

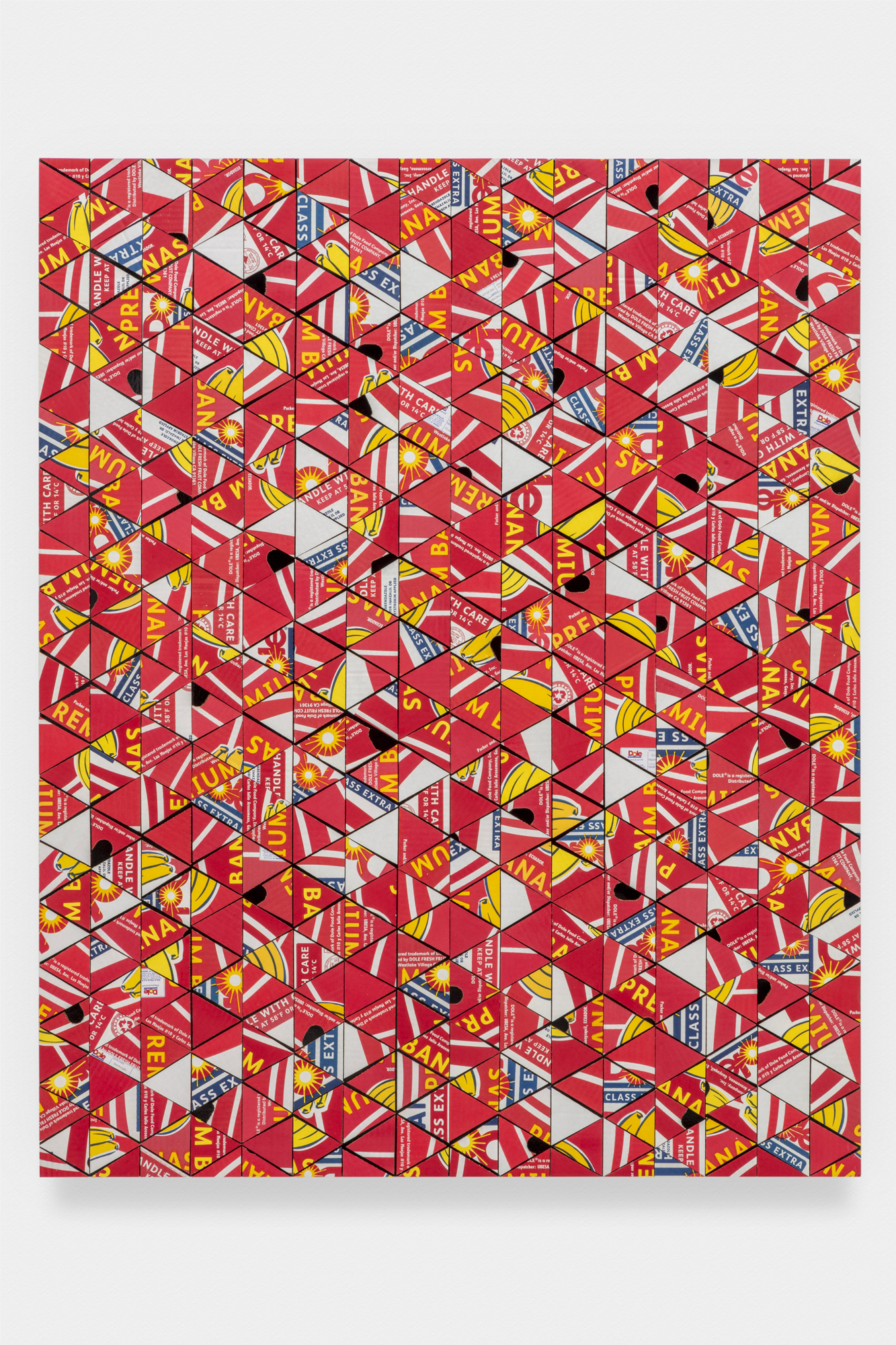

Jebila Okongwu

Jebila Okongwu critiques stereotypes of Africa and African identity and repurposes them as counterstrategies, drawing on African history, symbolism and spirituality. One of his preferred materials is banana boxes; their tropicalized graphics articulate an ‘exotic’ provenance, much like the exoticization of African bodies from an ethnocentric perspective. When these boxes are shipped to the West from Africa, the Caribbean and South America, old routes of slavery are retraced, accentuating existing patterns of migration, trade and exploitation.

He is represented by Baert Gallery in Los Angeles.

Samuelle Richardson

Samuelle Richardson is inspired by Diego Rivera’s papier-mâché figures. She developed a sculptural technique using repurposed cardboard, shredded mail, staples, and glue—materials central to the classical-figure works in this exhibition.

Samuelle Richardson

Samuelle Richardson is inspired by Diego Rivera’s papier-mâché figures. She developed a sculptural technique using repurposed cardboard, shredded mail, staples, and glue—materials central to the classical-figure works in this exhibition.

Samuelle Richardson

Samuelle Richardson is inspired by Diego Rivera’s papier-mâché figures. She developed a sculptural technique using repurposed cardboard, shredded mail, staples, and glue—materials central to the classical-figure works in this exhibition.

Samuelle Richardson

Samuelle Richardson is inspired by Diego Rivera’s papier-mâché figures. She developed a sculptural technique using repurposed cardboard, shredded mail, staples, and glue—materials central to the classical-figure works in this exhibition.

Samuelle Richardson

Samuelle Richardson is inspired by Diego Rivera’s papier-mâché figures. She developed a sculptural technique using repurposed cardboard, shredded mail, staples, and glue—materials central to the classical-figure works in this exhibition.

Samuelle Richardson

Samuelle Richardson is inspired by Diego Rivera’s papier-mâché figures. She developed a sculptural technique using repurposed cardboard, shredded mail, staples, and glue—materials central to the classical-figure works in this exhibition.

Narsiso Martinez

Narsiso Martinez’s drawings and mixed media installations include multi-figure compositions set amidst agricultural landscapes. Drawn from his own experience as a farmworker, Martinez’s work focuses on the people performing the labor necessary to fill produce sections and restaurant kitchens around the country. Martinez’s portraits of farmworkers are painted and drawn on discarded produce boxes collected from grocery stores. Martinez makes visible the difficult labor and onerous conditions of the “American farmworker,” itself a compromised piece of language owing to the industry’s conspicuous use of undocumented workers. - Charlie James Gallery

Frank Gehry

The Wiggle Side Chair is part of Frank Gehry’s 1972 furniture series ‘Easy Edges’, in which he succeeded in bringing a new aesthetic dimension to such an everyday material as cardboard. The sculptural chair is not only very comfortable, it is also strong and robust. It currently in production at Vitri in Basel Switzerland.

“I love working with materials directly. The cardboard furniture allowed that to happen. I could design a shape and build it in the same day. Test it. Refine it. And the next day build another one.” -Frank O. Gehry

“Cardboard furniture. What an albatross. Boy did I get myself in trouble with this one! It grew out of the need to find something cheap and disposable for fixtures. I started experimenting with cardboard in all the ways one would think of it in terms of efficiency; folded sheets make a structure very economically. Somehow, when you made something, it wasn’t very nice. It was folded cardboard. Then one day I was looking at architectural contour models, which were layers of cardboard. I was looking at the end elevation with its combed look, and I got excited about it. I started to see it as an aesthetic opportunity, and I made the desk I still use.” -Frank O.Gehry

Frank Gehry

The Wiggle Side Chair is part of Frank Gehry’s 1972 furniture series ‘Easy Edges’, in which he succeeded in bringing a new aesthetic dimension to such an everyday material as cardboard. The sculptural chair is not only very comfortable, it is also strong and robust. It currently in production at Vitri in Basel Switzerland.

“I love working with materials directly. The cardboard furniture allowed that to happen. I could design a shape and build it in the same day. Test it. Refine it. And the next day build another one.” -Frank O. Gehry

“Cardboard furniture. What an albatross. Boy did I get myself in trouble with this one! It grew out of the need to find something cheap and disposable for fixtures. I started experimenting with cardboard in all the ways one would think of it in terms of efficiency; folded sheets make a structure very economically. Somehow, when you made something, it wasn’t very nice. It was folded cardboard. Then one day I was looking at architectural contour models, which were layers of cardboard. I was looking at the end elevation with its combed look, and I got excited about it. I started to see it as an aesthetic opportunity, and I made the desk I still use.” -Frank O.Gehry

Ann Weber

Ann Weber began working with cardboard in 1991 after an early career as a potter producing functional wares in Ithaca, New York, and later in New York City. Inspired initially by Frank Gehry’s cardboard furniture, she turned to the material for its immediacy, accessibility, and sculptural potential. For permanent outdoor installations, she casts her cardboard originals directly into bronze, translating the material’s texture and spontaneity into enduring form. At the core of her practice is a commitment to pushing the boundaries of a common, sustainable material and uncovering the elegant, unexpected possibilities it contains.

Leonie Weber

“For the exhibition at Wönzimer I flew to California to create the piece in Ann Weber’s studio. We are distant cousins. The boxes, even though bent and distorted, remain recognizable as such, their shapes nestled against and into each other. This work is the distilled result of a longer occupation with the online retailer Amazon, and the labor involved in online shopping, in the warehouse and the distribution but also in the domestic realm. The action of recycling used cardboard is both a part of domestic labor as well as the care and maintenance of the planet, however futile that might seem in an economy that consumes such massive amounts of cardboard.” – Leonie Weber

Shigeru Ban

Once described as the “accidental environmentalist,” Shigeru Ban was born in Tokyo in 1957 and studied the at SCI-Arc (Southern California Institute of Architecture) for two years before earning a Bachelor of Architecture at The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art in New York City. He founded Shigeru Ban Architects (SBA) in 1985 and later established offices in New York and Paris.

For over forty years, Ban has developed a unique structural system using recycled paper as a building material and, alongside his architectural work, has been engaged in disaster relief efforts worldwide. In 1995, he founded Voluntary Architects’ Network (VAN), a non-governmental organization that has designed and constructed more than 50 relief projects worldwide, across 6 continents.

Edgar Ramirez

“Drawing on his immediate urban environment, certain pockets of art history, and Post-Fordist philosophy, Edgar Ramirez is an atypical painter. The subject matter of his work is inspired by the anonymous signs– We Buy Houses, Fix Your Credit, etc– that parasitically populate low-income neighborhoods all over Los Angeles, as well as America. Appropriating the look and language of these predatory signs, he paints them in a multitude of colors on cardboard and then subjects them to a process of aggressive subtraction which seems to exist somewhere between classical décollage and urban decay.” – Chris Sharp

Edgar Ramirez

“Drawing on his immediate urban environment, certain pockets of art history, and Post-Fordist philosophy, Edgar Ramirez is an atypical painter. The subject matter of his work is inspired by the anonymous signs– We Buy Houses, Fix Your Credit, etc– that parasitically populate low-income neighborhoods all over Los Angeles, as well as America. Appropriating the look and language of these predatory signs, he paints them in a multitude of colors on cardboard and then subjects them to a process of aggressive subtraction which seems to exist somewhere between classical décollage and urban decay.” – Chris Sharp

Edgar Ramirez

“Drawing on his immediate urban environment, certain pockets of art history, and Post-Fordist philosophy, Edgar Ramirez is an atypical painter. The subject matter of his work is inspired by the anonymous signs– We Buy Houses, Fix Your Credit, etc– that parasitically populate low-income neighborhoods all over Los Angeles, as well as America. Appropriating the look and language of these predatory signs, he paints them in a multitude of colors on cardboard and then subjects them to a process of aggressive subtraction which seems to exist somewhere between classical décollage and urban decay.” – Chris Sharp

Michael Stutz

: It was through the experience of designing and creating Mardi Gras floats in New Orleans that Michael Stutz discovered cardboard as a creative medium. The structural methods used in float construction inspired him to experiment with the material in his own art. Upon returning to San Francisco, he began crafting sculptures from reclaimed cardboard—often using packaging from items he personally consumed—coiling and weaving strips into intricate patterns that formed bold, expressive figures.

Over the past 25 years, Stutz has created more than 40 public art projects across the United States and Europe. His monumental bronze sculptures continue the woven aesthetic of his early cardboard work, transforming the material’s fluid, interlaced structure into enduring forms that celebrate the vitality of nature, humanity, and craft.